We are pretty poor in Ireland at properly describing the state we are in, both physically and psychologically. We live in a political state that we describe as a ‘republic’ even though it patently fails to meet the test for a republic and is, instead, something else, but we won’t name it for what it really is. And we live in a state of being, a psychological condition strangely common across disparate groups that each claim to draw inspiration from widely differing sources, whether christian or non-christian religious faiths, various right-wing or left-wing political faiths, those of no religious or political affiliation and so on. Despite those different influences, so deeply important to many individuals, we act – or fail to act – as if we are all of the same mind.

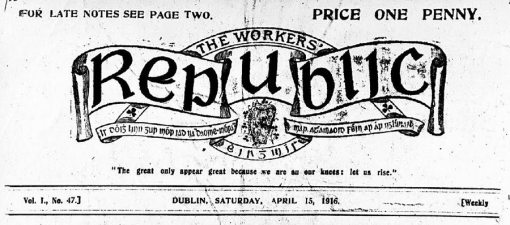

First to the political state we are in, the so-called ‘republic’. A reasonable person might imagine that our definition of ‘the republic’ should derive from the foundational document of the independent Irish State, the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. Paragraph four of the Proclamation lays out very clearly the relationship between the republic and its citizens and the rights and freedoms that the citizens would enjoy.

‘The Irish Republic is entitled to, and hereby claims, the allegiance of every Irishman and Irishwoman. The Republic guarantees religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens, and declares its resolve to pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole nation, and of all its parts, cherishing all of the children equally, and oblivious of the differences carefully fostered by an alien government, which have divided a minority from the majority in the past.’

The document is revolutionary in its proposal to bring about profound change to the existing order under British rule. It fueled the War of Independence, and its terms were ratified by the people through the elections of 1918, and in the Declaration of Independence issued by the first Dáil in 1919. It is the template for our Irish Republic. But something went wrong. Instead of being our guiding light, the Proclamation was hung, face to the wall, in the darkest corner the state could find.

The Civil War which followed ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1922 which was forced through by the British under threat of ‘immediate and terrible war’ has had a hugely distortive effect on Irish political life ever since. The victors in that Civil War, the pro-Treaty Free State government, was made up of businessmen, professionals and middle-class conservatives. The anti-Treaty side contained the bulk of those radicals and socialists who had survived the Revolution in 1916, and who had prosecuted the War of Independence against the British to establish the Irish Republic. Most of the women who had taken an active part in the 1916 revolution and the War of Independence were on the anti-Treaty side.

Seventy-seven captured anti-Treaty ‘Irregulars’ were executed by the Free State government in 1922-23, some on the flimsiest of charges, and some by summary execution without trial. Republican heroes including Erskine Childers, Liam Lynch, Rory O’Connor and Liam Mellows (acknowledged as a socialist intellectual of the same calibre as James Connolly) were executed by Free State firing squads both as a reprisal for acts done by others over whom they had no control, being in prison, and as a way of permanently removing an oppositional cadre of high-quality and deeply committed leaders. The mindset of those government ministers who set this brutal and unlawful campaign of terror in place would later reveal itself as proto-fascist with the amalgamation of their party Cumann na nGaedhael with the fascist Army Comrades Association, better known as the Blueshirts, to form the Fine Gael party that leads the current government.

A principal icon of that party, William T Cosgrave, who was the first prime minister of the Free State, encapsulated that mindset in this quote from a letter he wrote to Austin Stack in 1921 – “People reared in workhouses, as you are aware, are no great acquisition to the community and they have no ideas whatsoever of civic responsibilities. As a rule their highest aim is to live at the expense of the ratepayers. Consequently, it would be a decided gain if they all took it into their heads to emigrate.” That contempt for the poor and marginalised, victims of class politics and consequent economic and cultural deprivation, is still evident in Fine Gael attitudes to this day. It represents the polar opposite of the Republic laid out in the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

Many of those on the anti-Treaty side who survived the Civil War were driven into exile, or forced underground, such was the atmosphere generated by the Civil War. As Carol Coulter, writing in 1990, put it: ‘The many other elements which were undoubtedly present in Irish nationalism – not just at the level of ideology, but expressed in living people – ranging from socialism and feminism to religious scepticism and various forms of mysticism, were defeated and their adherents marginalised or forced to keep their dissident views to themselves.’

Eamon de Valera, who was the political leader of the anti-Treaty forces, and who created the Fianna Fail party in 1926 ostensibly as ‘The Republican Party’, would consistently show himself from then on, as he had in 1916, to be nothing more than a catholic nationalist and certainly not a republican. He had been the only 1916 commandant to escape execution, and the only one to have refused to have women as part of the garrison he led (at Boland’s Mills). That decision he later regretted solely on the grounds that some of his men had to cook! In his political life over many years as Taoiseach and later president, de Valera demonstrated no desire whatever to elevate the Proclamation from obscurity by creating the very Irish Republic that he had sworn in 1916 to put into place.

Having ‘won’ the Civil War, the Free State government set about dismantling the revolution and creating what can only be described as the counter-revolution – the very danger that James Connolly had warned against on many occasions leading up to the 1916 revolution.

The perpetuation of the highly-centralised state administrative system closed off access to power from the broad mass of ordinary people. The professional classes, property owners, capitalist industrialists and bankers still had that access, and the influence that went with it. So too had the Roman Catholic Hierarchy.

As a result of partition, and the consequent separation from the largely-Protestant North East, the Catholic Church held a powerful position in the Free State and began to assert its moral authority more explicitly. Within eight years, what can be described as Catholic legislation had found its way onto the statute books, with discriminatory laws on illegitimacy, divorce, contraception and censorship.

The Film Censorship Act (1923) was passed very shortly after the transfer of power to the Free State government. At this stage the Irish economy was in tatters. The nation had just endured a deeply divisive civil war. Child mortality rates were frighteningly high by European standards. Large numbers of people existed in the most squalid conditions both in the cities and rural areas. And yet the censorship of film was deemed important enough to be placed high on the list of legislation.

‘The highly authoritarian, anti-intellectual strain of Irish Catholic morality was incorporated in the Censorship of Films Act (1923) and the Censorship of Publications Act (1929). These acts were rigorously enforced up to the 1960s by a Censorship Board which was vigilantly supervised by Catholic lay organisations such as the Knights of Columbanus’. (Tom Inglis: ‘Moral Monopoly’)

The censorship of books and magazines was undertaken on the grounds of ‘public decency’ or ‘obscenity’, but played a major role in suppressing the availability of information to women on matters that apply particularly to them, such as contraception and abortion. Frank O’Connor summed up the situation in 1962 in a debate in Trinity College Dublin: ‘What really counts is the attitude of mind, the determination to get at sex by hook or by crook. Sex is bad, books encourage sex, babies deter it, so keep the books out and give them lots of babies, and we shall have the nearest thing the puritan can hope for to a world without beauty and romance’.

While radicals, dissidents, the poor and the consumers of literature and the arts lost heavily because of the dominant counter-revolutionary ideology of the Free State, there can be no doubt that it was women who bore the brunt of a patriarchal assault on their civil liberties and their sense of self-worth. As soon as the Treaty had been ratified the war on women began. The Catholic Church had created a process of social control and social engineering in the nineteenth century based around the mother as the link to the individual, and one of the principal ways in which the Church exercised control over the mother was by exercising control over their sex.

‘In Ireland, it was the knowledge and control that priests and nuns had over sex which helped maintain their power and control over women. Women especially were made to feel ashamed of their bodies. They were interrogated about their sexual feelings, desires and activities in the confessional. Outside the confessional there was a deafening silence. Sex became the most abhorrent sin.’ ( Tom Inglis ‘Moral Monopoly’)

But the State was now playing its part through the legislative process. Women were increasingly excluded from the public sphere, and were by law precluded from exercising artificial means of control over their own reproductive organs. Single women who made the ‘mistake’ of becoming pregnant were vilified or exiled. Many ended up in the now infamous Magdalene Laundries run by the religious orders, along with many other girls and young women who were considered by the clergy, police or their families to be ‘at risk’. Very many of these unfortunates spent their entire adult lives in these awful places.

In the same way that ‘at risk’ girls, or ‘fallen’ women, could likely end up in the Magdalene Laundries or similar institutions, children who were ‘deviant’ through an involvement in petty crime, poor school attendance, or lack of parents – in other words, orphans – were certain to find themselves in the euphemistically titled ‘Industrial Schools’ run by the Christian Brothers, or an equivalent institution for girls. The State washed its hands of responsibility for these, the most vulnerable in society.

The consequences of that policy are now coming to light in proven cases of physical, psychological and sexual abuse on a horrifying scale. These children were not cherished equally to the children of the middle class and the bourgeoisie, but those who abused them, and those who facilitated the abusers in the Catholic Church, the Irish civil service and police, the medical and legal professions and politicians have, by and large, remained untouched by the law.

The 1937 Constitution was another retrograde step foisted on women. Women were now mentioned only as ‘mothers’ and their assigned space was to be the home. The constitution envisaged that women would not, through economic necessity, neglect their primary duties to their husband and their children by working outside the home. Of course many families could not rely on the father’s capacity to provide a living wage, so that for many in Ireland this was just another pious platitude.

‘The position of women in the Irish constitution is value laden. I think it really comes from the central position that the Catholic Church occupies in the Irish Free State and the perception of women in catholic cultural and political life, and this very often happens in a country that has undergone a revolution followed by a civil war, that the strong currents regulating the life of the country go towards a desire for conservative behaviour and conservative images of women’. (Historian Margaret McCurtain).

Women had played a major part in the republican and trade union movements. They had been actively involved in the Land League, Gaelic League, Celtic Revival, the Howth Gun-Running, the 1916 Rising, the War of Independence, and the Civil War. They had been amongst the most committed to the cause of Irish freedom, and had been formally included in the Proclamation. But in the new Ireland, they were to be mothers, menial workers or minders.

In the significant areas of health and education the degree of control which the Church had achieved in the nineteenth century under British rule was augmented under the Free State regime. Control of health through hospitals and clinics with a strictly catholic ethos, is another way, outside the confessional, of exercising control over the body.

When the then Minister for Health, Dr. Noel Browne, attempted to bring in the Mother and Child scheme in 1951, which was to do with nothing more than the provision of health care for pregnant women and post-natal care for mothers and children, the response from the Hierarchy took the form of a letter to the Taoiseach – ‘To claim such powers for the public authority, without qualification, is entirely and directly contrary to Catholic teaching on the rights of the family, the rights of the church in education, the rights of the medical profession and of voluntary institutions’

The Minister was forced to resign, and the Mother and Child scheme fell.

In the area of education, the State likewise abrogated its responsibilities to the Church. The Church was, just as it had been under British rule, delighted to – indeed insistent that it should – fill that vacuum. Under Catholic Church control, equality of educational opportunities was not to apply to all of the children of the Nation, just all of the children of the bourgeoisie.

‘It suited this class down to the ground to entrust the education of the youth, and the formulation of social policy, to the Catholic Church. The outlook which it put forward in the 1930s with its corporate view of society, sought to deny class divisions, to preach satisfaction with the economic status quo, and to keep women and youth subordinated to husbands and fathers.’ (Carol Coulter)

Irish education is based on the notion of conformity, and conformity is a vital element in a hegemonic system. According to UCD historian David Fitzpatrick, Catholic nationalism was promoted by the Christian Brothers through ‘the most systematic exploitation of history’ and that their Irish History Reader of 1905 claimed that ‘a nation’s school books wield a great power’, and further: ‘Teachers should reinforce the text-book’s message by dwelling “with pride, and in glowing words on Ireland’s glorious past, her great men and their great deeds”, until pupils were persuaded “that Ireland looks to them, when grown to a man’s estate, to act the part of true men in furthering the sacred cause of nationhood’.

Fitzpatrick further points out that while the writings of Protestants such as John Mitchel and Thomas Davis were popular at the time, the Christian Brothers publication ‘Our Boys” entreated that pupils who were establishing libraries in Christian Brothers’ schools should ‘..be sure, though, that everything you get is recommended by a good Catholic Irishman’.

One important agent of influence in the state was outside direct and overt control by the Catholic church. But since the church directly influenced almost all of those who owned or worked in the media it could rest assured that its views would fall on friendly ears and be delivered through TV, radio and the printed press to the mass of Irish people. Since the vast majority of Irish politicians and state employees such as civil servants and the army and police were loyal, and sometimes fanatical, members of that church, it was in the interest of the state and its employees that those Catholic Church views on almost all important social issues were reported, and reported favourably. After all, maintaining the status quo was in all of their interests – although not in the interest of the mass of people.

Writer and cultural philosopher Desmond Fennell summed it up well in 1993: ‘When an ideological sect has a monopoly of the national media, it tends inevitably, without need of conscious decision, to prevent or minimise public discussion of those ideas it does not want discussed.’ Thus, in the interest of maintaining the status quo, discussion of republican, socialist, feminist, secular and other dissenting views – in other words, progressive ideas – was to be curtailed, or better still prevented, lest those ideas lead to a change in the social order.

The media audience was thus culturally conditioned into belonging to a community, the values of which did not evolve organically over time and through informed and free consent, but were a consequence of inputs under the control of the political class, i.e. the bourgeoisie which combined willingly with the Catholic hierarchy, to create, to use Fennell’s term, an ideological sect.

It is only in the past 20 years or so that the ruling ideological sect has begun to be challenged, and mainly through the work of a small number of ethical journalists, the persistence of a few leftist political groups and individuals, and the work of a few members of the legal profession. Their targets have been, in the main, the political and civil institutions of the state, and the Catholic church.

As far back as 1994, Fintan O’Toole wrote that: ‘In Ireland, virtually every branch of the political system has had its inadequacies exposed. Neither the systems of thought nor the systems of government can simply be patched and mended. They need to be reimagined, redrawn and reconstructed.’

In recent years there has been a steady trickle of information emerging about the relationship between the political and the commercial worlds, triggering a series of interesting but essentially ineffective public inquiries. Ineffective, since prison does not seem to be an option for patently corrupt politicians or businessmen or professional facilitators of corrupt practices.

Neither do the jail gates swing open to receive ecclesiastical prisoners – the bishops and other high-ranking priests and members of the institutional Catholic church – those who destroyed or hid evidence of the most egregious abuse of children, who deliberately lied about crimes they knew to have been perpetrated. In this non-republic there is one set of laws, rigorously applied, for the poor and marginalised and vulnerable, and there is a very different set of rules for the professional class, the Catholic hierarchy and its collaborators, politicians, and the business community.

And so to the Irish State, and what it really is. It is patently obvious that it cannot be described, from its foundation to the present day, as a republic. A republic is the property of its citizens, according to Cicero, and post-Enlightenment republics generally aspire to that idea.

The Irish State has been owned from 1922 to the present day by Desmond Fennell’s ‘ideological sect’, or to put it another way, the priests and the political class of which they form part.

The best description of the Irish State is that it was first a counter-revolutionary theocratic state controlled in its essence by an ultra-conservative religious sect, and that it has, with the diminution in power of the Irish Catholic Church over the past 30 years, become a counter-revolutionary plutarchy – a combination of plutocracy (government by a wealthy class) and oligarchy (government by a dominant class or clique) – a plutarchy determined at all costs to stifle the beautiful vision of the Proclamation.

And what of the people of Ireland, or at least of the 26-county Irish State, and their seeming inability, in general, to act politically and socially in different ways depending on their particular ‘faiths’ whether religious or political, to rationally debate different ideas, to come to different conclusions, make different choices, act with some evidence of individual autonomy and reason?

How is it that a majority of people in this state consistently act against their own economic or social interests in electing a set of political parties to govern, knowing from experience that the inevitable outcome will be the pampering of the wealthy at the expense of the lower middle and working classes and the poor, and the formulation of social policy so as to achieve as little progressive movement as necessary, thus securing the existing social order?

How is it that in the face of outrageous and generally un-prosecuted crimes committed against women and children, and the corruption of political institutions by politicians, professionals and business interests, the people give out and then, inevitably, give in?

How is it that the mass of ordinary people, workers and their families, with all of the evidence around them of a contempt for the contribution they make to the companies they work for, and to the State itself, give in to a campaign of vilification of the trade union movement – the very institution that gave them the 40 hour working week, annual leave, legal and regulatory protections, a seat at the negotiating table, a minimum wage, extra pay for unsocial hours and redundancy compensation?

The answer to these questions lies in understanding that classic ‘civil war to counter-revolution’ scenario described earlier by Margaret McCurtain, and adding to it the deliberate creation off a hegemonic state by creating a ‘spiral of silence’ in which all dissident views are regarded as deviant and dangerous and contrary to ‘public good’ and even the ‘natural order’.

The evidence is all there in full view. It is time for us to understand it and to react rationally in our own interest and in the interest of the common good. It is time for us to start naming things for what they really were and are. It is time for us to stop using ambiguity in language as it applies to public life and to the nation, to stop talking from behind our hands, to stand up and speak out, to stop giving out and then giving in. It is time for us to tear back the Proclamation from the dead hands of that ugly ‘ideological sect’ and to put it into action for the benefit of all citizens – to re-create the Republic.

It is time for us to grow up.